Distances in Reflection: Between illusion and truth

Hiroshi Sugimoto once said, “What the eye sees is not what the camera sees.” That thought lies at the heart of Distances in Reflection, but in truth, it runs through all of my work.

When I took this shot, I was out in the kayak, close to the hull of a boat. My process is always improvisational—I lift the camera, point, click, and by the time the shutter opens, I’ve already drifted past what I thought I was framing. Later, when I looked at the image, I was startled. What I saw on the screen felt utterly different.

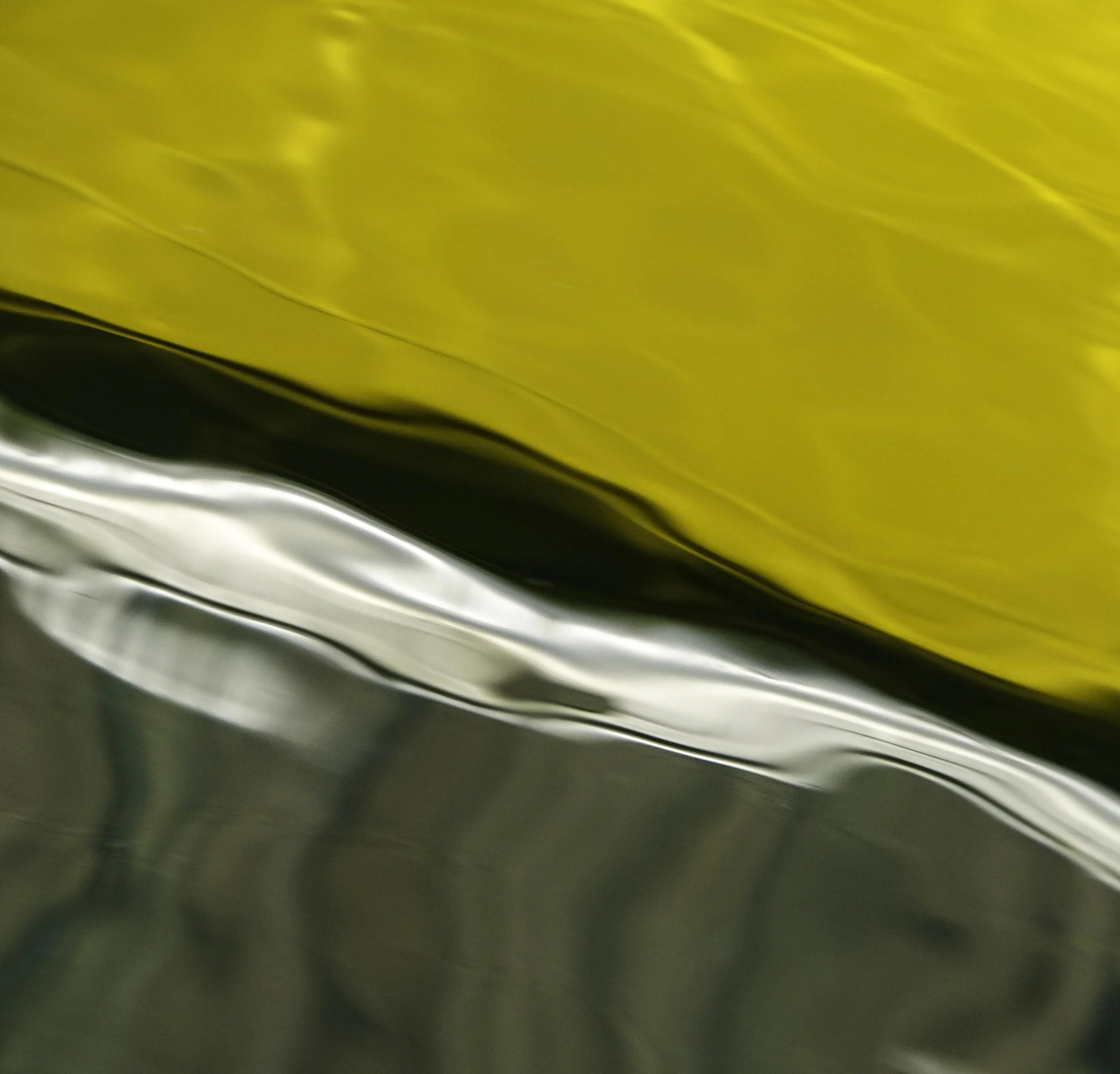

At first, I was struck by the Rothko-like expanse of yellow. It carried the same weight of abstraction—large, immersive, emotional fields of colour. Then my eye caught the white edge, like breaking waves against a shoreline. And gradually, the whole thing began to read like an aerial view, as though I were high above looking down on an offshore coast.

And here’s the paradox: in one sense it’s an illusion, but in another it’s true. I was offshore, floating on water, and when I leaned over to capture the reflection, I was aerial too. The metaphor folds back into reality. What the camera gave me was not simply what I saw, but something transformed—a proposition to see differently, to hold the work as both truth and illusion at once.

This aesthetic illusion is something I’ve come to recognise as central to my practice. In Paintings on Water, the reflections were so painterly that the boundary between photograph and painting dissolved. In the Sand Talk Collection, Sydney sandstone and water conspired to create patterns that echoed Aboriginal desert paintings, carrying memory and cultural resonance far beyond what I had consciously seen. And in the Offshore Aerial Collection, the water’s surface revealed vast coastlines and sweeping geographies that could have been seen from thousands of feet above, yet were born entirely from reflections at sea level.

Distances in Reflection belongs to this same continuum. My role as an artist is not to stage or to control, but to mediate: to accept what the camera and the water offer me, to cut and frame, and then to place the work in a space where others can see and experience it.

Every artwork I create, then, becomes more than an image. It is a proposition—an opening into another way of seeing. What begins as a fleeting reflection on the water becomes an invitation for others to pause, to question, and to wonder: what am I really looking at?

That is the practice I am developing. Not simply documenting the world, but working with water, reflection, and chance as a way of thinking about perception itself.