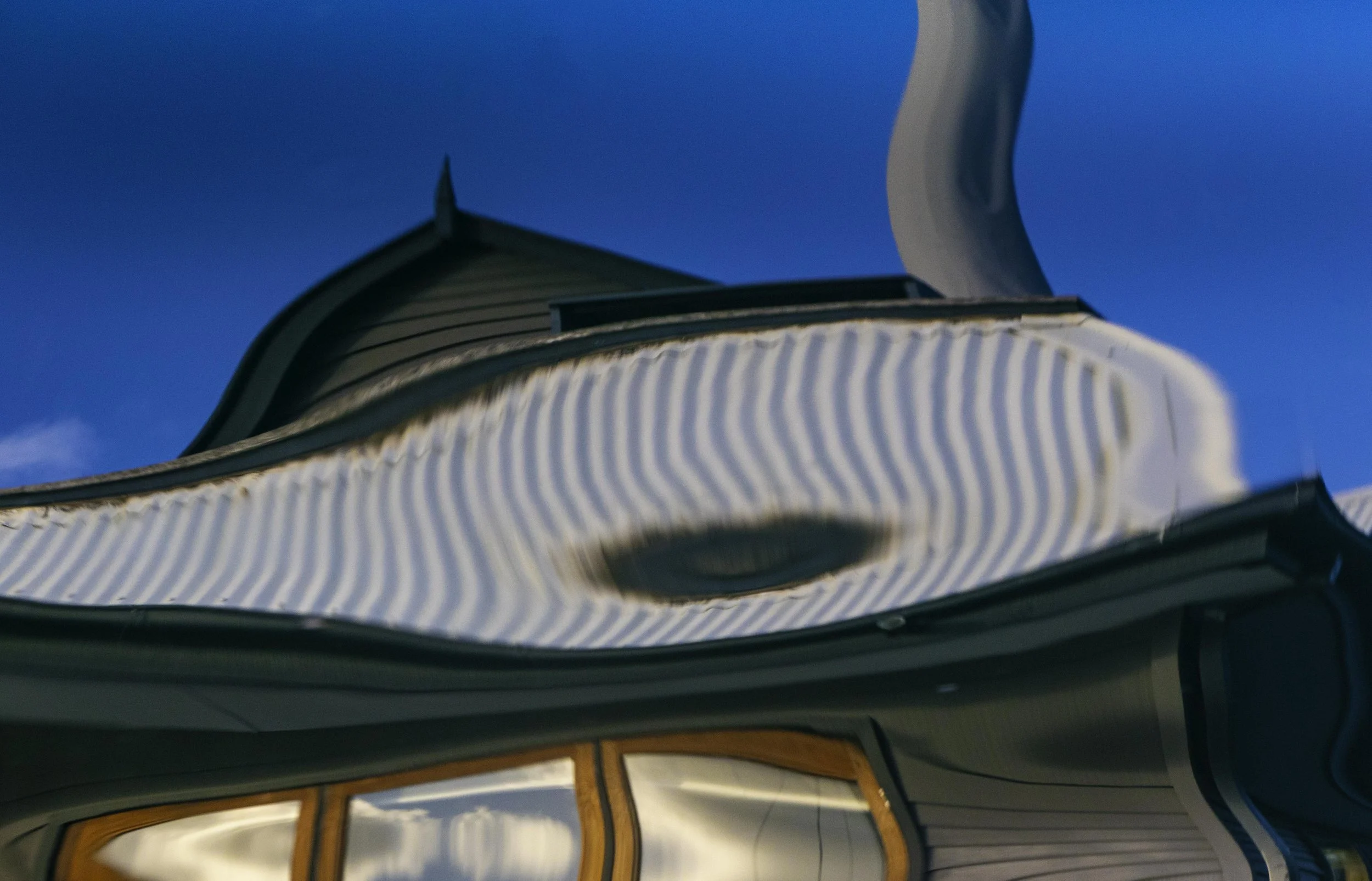

Surreal Estate: When a Boatshed Grew an Eye

I sometimes wonder if I’ve become a “water surrealist.” Out on my kayak in Middle Harbour, I drift with the camera ready, waiting for reflections to do their work. One moment the surface is calm, the next it throws up a vision so strange, so dreamlike, that it feels deliberately crafted. Yet it is entirely accidental, gone in an instant.

This boat shed was one of those moments. Normally plain, even modest—a functional structure perched on the water’s edge. But in its reflection it became something altogether different. The striped cladding bulged and curved as though the shed itself were breathing. The apex of the roof twisted into a playful wave, like a structure shrugging off its straight lines. And in the middle, a pale blue ripple formed a perfect oval: an eye. Suddenly the shed wasn’t a shed at all—it was alive, looking back at me.

The Surrealists would have recognised this transformation. André Breton spoke of creating a “crisis of the object,” where ordinary things lost their certainty. René Magritte painted houses and skies to unsettle our trust in appearances. Salvador Dalí melted the solid world into fluid absurdity. Their work was painstakingly imagined, constructed from dream logic and paradox. What I encounter on the water, by contrast, is unplanned. Yet when a reflection reshapes a shed into a sentient form, the effect is startlingly close.

That’s when the title came: Surreal Estate. It made me laugh, but it also felt inevitable. Sydney is famously obsessed with property. Auctions, renovations, record prices—it’s the city’s great fixation, the fuel of conversation at cafés and dinner parties alike. Even the humble boat shed carries cultural weight, a badge of status on the waterfront. And here, on Middle Harbour, that status symbol dissolved into absurdity. The shed breathed, warped, and grew an eye, as though the harbour itself were mocking our seriousness.

The Surrealists loved puns and wordplay, seeing humour as a way to shake us out of habit. Duchamp’s readymades, Magritte’s sly inscriptions, Dalí’s flamboyant titles—all remind us that language can be as unstable as vision. Surreal Estate follows in that tradition. It is both a pun and a provocation: a playful title for a fine art photograph that undermines our faith in the permanence of bricks, mortar—or even weatherboard.

Yet humour is only the beginning. The image also suggests something more profound: that surrealism is not confined to human invention. Out here, on the harbour, it arises naturally. The reflections distort, animate, and—at least for a moment—become sentient. And sometimes, as with this shed, they turn the tables and look back.